I’ve always been told to relax my shoulders when running. This is great advice, but this isn’t all we runners can relax while running…

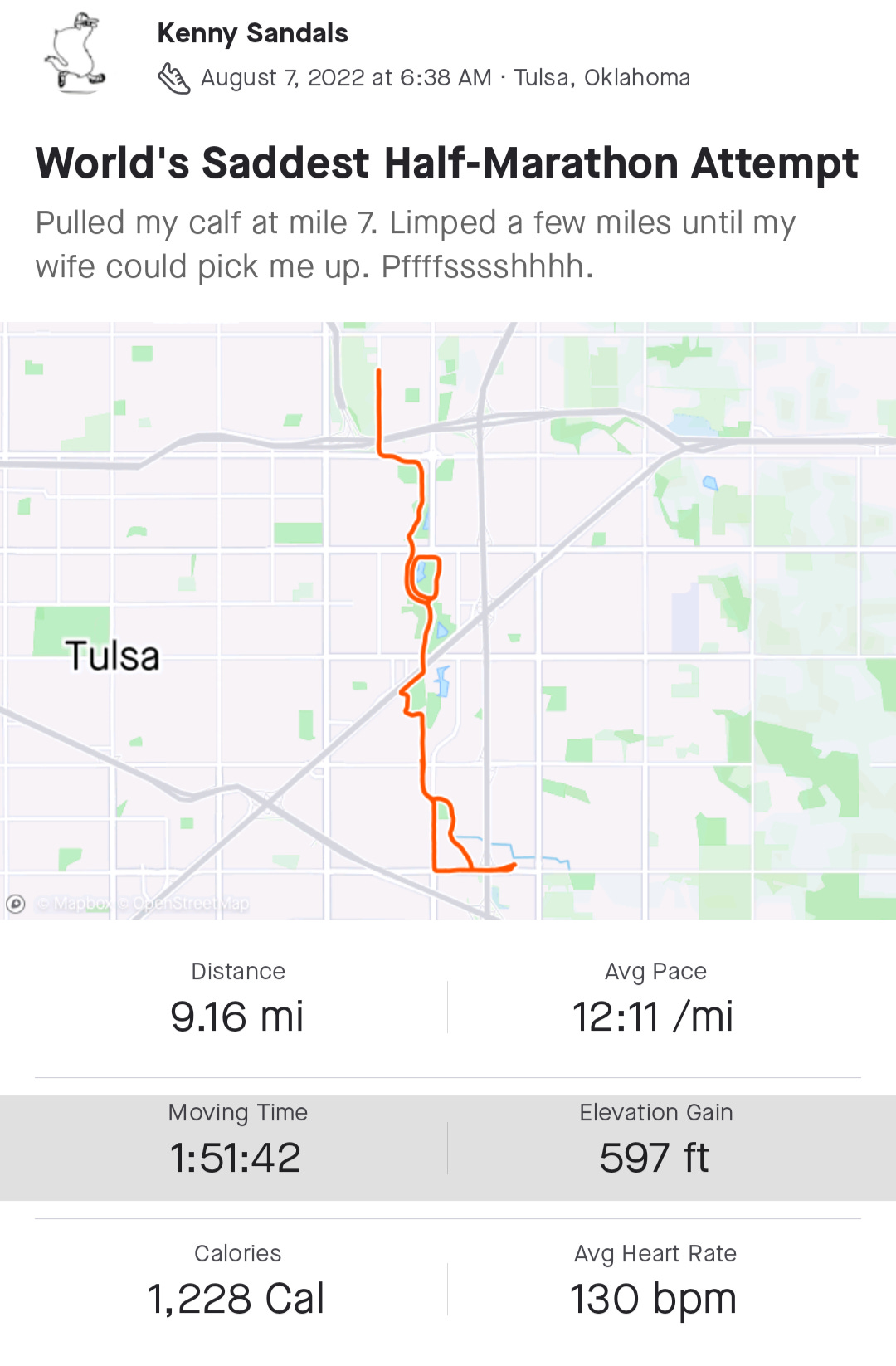

About 10 days ago, while in the middle of what would have been about a 14-mile out-and-back run, my left calf tensed up immensely. A little further along, I felt a hard pop in that calf and every push-off felt like a charlie horse. Dang it—I had torn my left calf muscle.

After about 9 days of recovery, I felt like I was ready to test the leg’s running abilities. But first—I tried to jump rope on it. And then…double-unders. Yowch. Lesson learned: don’t do that.

All Aboard the Struggle Bus

I decided to attempt a modest run. I could immediately tell that the calf wasn’t 100%, but that surely I could manage 5k.

The further I went, the tighter the calf got. I stopped every mile or so to massage out some of the tension. I also found myself getting tired because of how much I was consciously babying the leg. That is…until I figured out a nice trick.

Your Legs Are Springs, Not Oxen

One of the mechanical features that make running sustainable is that your legs are really only working half of the time—and are more like two springs instead of two jacked oxen pulling the wagon down the trail.

If you’re using proper technique, the natural tension of the leg, when loaded with your forward momentum (and maybe a dash of body weight) should provide enough spring to launch you forward without much conscious push from your leg muscles. As your body is launched forward by your natural springs, your leg will hitch a ride with it without the need for you to “drive your knees.”

If you’re consciously pulling your leg forward with its muscles while it is off the ground instead of letting the released tension bring it forward, your leg never really gets a break. Your calf and quads remain highly engaged when not working to carry the rest of your mass forward. The result? Tight muscles, tendons, and ligaments just dying for a break.

The answer? Give ‘em a break, you dingus.

Embrace the Flop

I didn’t realize just how much unnecessary work I was giving my legs until my legs let me know. Why was my heart rate over 160bpm while running at almost a 10-minute-per-mile pace? Ah, yes—I was keeping my legs tensed up while they weren’t even on the ground and they were not happy about that.

As I realized this, I consciously relaxed my legs as much as possible when they weren’t touching the ground.

Land. Glide. Flop.

Land

First, I would focus on landing with a splayed, supportive foot under my pelvis—contact first occurring around the midfoot, letting raised toes fall to support the metatarsal heads, and the heel kiss the ground all in a near-simultaneous connection.

Glide

Second, the “glide” contains both the process of supporting incoming loaded energy and the release of that energy. As weight and momentum load up the leg like a spring, I’d use the foot, ankle, shin, knee, quad, glute, hip, and torso muscles to stabilize and support my forward momentum. It is the release of this spring that propels me forward—not in a conscious pushing, but in a returned supported unfurling or unleashing of energy.

Acceleration beyond what your natural springs can provide can be achieved with additional help from the muscles—just pushing ever so slightly to achieve greater “hang time” between foot landings. Just make sure to keep landing under your pelvis, ok?

Flop

Once your leg has released its energy and your forward momentum allows it to take flight, you can consciously cut the ignition from it. If you have the appropriate momentum and your landing, loading, and release were efficient, the muscles in the leg can afford to clock out until your foot meets the earth again. A combination of momentum, tendons, ligaments, and joints will bring the foot back into position for its next landing.

Slack Airborne Ankles

I like to take the flop one step further and let my ankle go slightly slack when not supporting my body. This not only helps lubricate the joint of the ankle without a load on it but also disengages the Achilles tendon and calf muscles to give them a break while they’re catching some hang time. This slackened ankle also provides greater proprioception of the foot on landing—allowing the foot to mold to the terrain and for the ankle to provide support at the correct angle.

Putting Them All Together

If I had been narrating my thought process as I ran, it would sound something like land-glide-flop, land-glide-flip, land-glide-flop, land-glide-flop.

Of course, it will take time before disengaging your airborne legs and “embracing the flop” becomes smooth and habitual. Only focusing on your “glide” foot will help you take your mind off your disengaged flying leg.

If you do not run with proper form (such as running with a heel strike), “embracing the flop” will likely not work and will result in you dragging a dead leg behind you. To be able to disengage your unused leg and allow your tendons to bring it back in proper landing position, proper form must be employed.

What is Proper Running Form?

While I hinted at some of the attributes of proper running form, laying out the tenets of proper running is a subject much too long for this essay. If you’d like to learn more about proper natural running form, I highly recommend reading Older Yet Faster by Keith Bateman and Heidi Jones.

This is not a paid endorsement. I’ve actually purchased this book twice—once on Kindle and once in the print version, which I recommend for easy consulting of various sections.